Africa's Debt and Illicit Financial Flows

This article was originally published by Africabrief on Apr 30, 2025

Kampala, Uganda—Africa's debt, estimated at $1.152 trillion by 2023, burdens over 25 countries, complicating sustainable development. IFFs, costing $80-90 billion yearly, stem from practices like corporate tax evasion and undervaluation in extractive industries, forcing governments to borrow more and deepen debt crises, writes Winston Mwale.

At the 11th Session of the Africa Regional Forum on Sustainable Development held in Kampala, Uganda, on April 30, 2025, Jason Braganza, Executive Director of the African Forum and Network on Debt and Development (AFRODAD), addressed journalists, highlighting Africa’s economic challenges.

His insights, shared during a press briefing, focused on the continent’s debt crisis, the pervasive issue of illicit financial flows (IFFs), and the transformative potential of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA).

Set against a backdrop of a polarized global economic landscape, his remarks underscored the urgent need for innovative financing and comprehensive debt reform to unlock Africa’s sustainable development.

The Debt Conundrum in Africa

Africa is grappling with a formidable debt crisis, with over 25 countries—more than half the continent—either in debt distress or at high risk. As of the end of 2023, the continent’s total external debt reached $1.152 trillion, a figure that has more than doubled over the past decade (African Debt Analysis).

This escalation is driven by a shifting creditor landscape, moving from traditional bilateral (country-to-country) and multilateral lenders like the World Bank, IMF, and African Development Bank to new bilateral lenders, such as China, and private commercial creditors.

These new creditors often prioritize short-term gains, complicating debt restructuring efforts.

Braganza emphasized the lack of a unified platform for African governments to collectively negotiate debt restructuring, stating, “What we're witnessing right now is a situation where African governments do not have a platform where they can collectively come together and negotiate and strategize on how they can restructure or renegotiate their debt dispensation with their creditors.”

This gap is critical in a “multi-polar and multi-crisis conundrum,” where global economic, political, and security dynamics further complicate negotiations.

The existing debt architecture, relatively constant over the last 20 to 25 years, struggles to adjust to this new creditor landscape, leaving countries reluctant to restructure debts for fear of losing access to international private capital markets.

Recent cases like Zambia, Ghana, and Ethiopia illustrate challenges due to outdated legal and policy frameworks, highlighting the need for robust domestic legislation (IMF Debt Crisis).

The impact is severe, with resources meant for public services—health, education, agriculture, water, and sanitation—diverted to debt servicing. In 2024, Africa paid out $163 billion just to service debts, up sharply from $61 billion in 2010 (AfDB Annual Meetings 2024).

This diversion undermines Agenda 2063 and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), stifling economic growth and job creation.

Braganza noted, “One major aspect that has also come up in the discussions this week is the diversion of resources from public investments, whether in public services, social services, or creating incentives for domestic businesses to flourish, is the diversion of those resources towards debt servicing.”

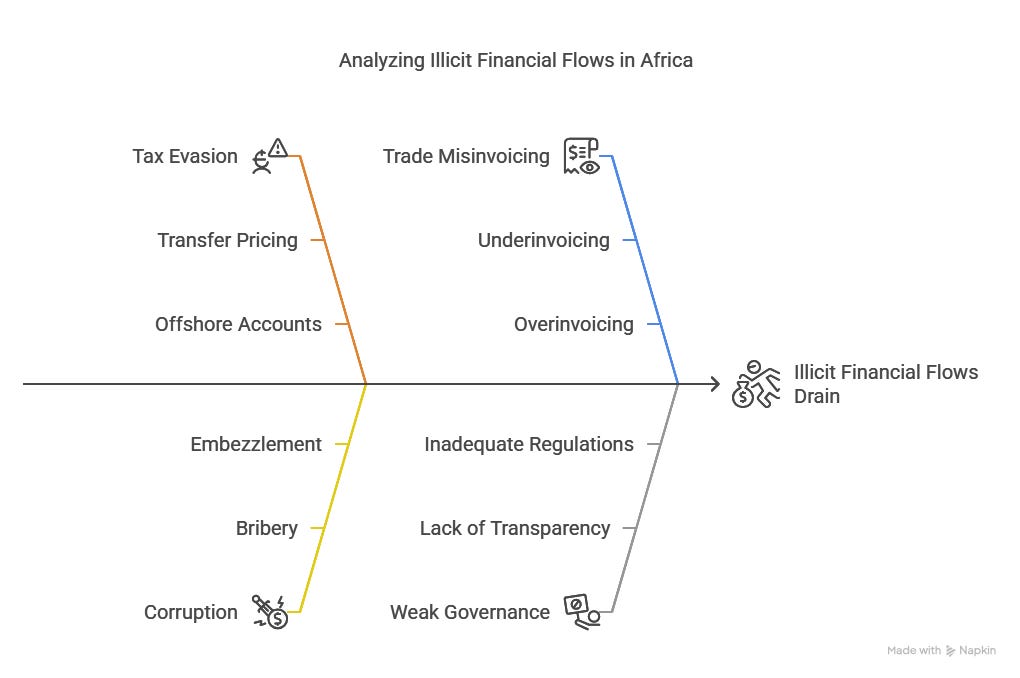

Illicit Financial Flows: The Hidden Drain

Illicit financial flows (IFFs) represent a significant drain on Africa’s resources, with estimates suggesting an annual loss of $80-90 billion, equivalent to 3.7% of the continent’s GDP (UNCTAD Economic Development in Africa Report 2020).

These flows, encompassing both legal and illegal activities, include tax evasion by multinational corporations, corruption, and mismanagement in the extractive sector. Braganza detailed three primary mechanisms:

- Tax Evasion: Multinational corporations establish subsidiaries in low-tax jurisdictions, shifting profits to avoid high African corporate tax rates (averaging 25-30%). This “tax planning,” or “tax efficiency” in corporate jargon, deprives governments of revenue.

Braganza explained, “When our governments provide incentives for foreign direct investment or for multinational corporations to set up operations, many of these corporations have subsidiaries or special companies set up in low-tax jurisdictions. These companies engage in tax planning, shifting profits to these low-tax jurisdictions and avoiding taxes in many African countries.”

- Extractive Sector Mismanagement: Resources are often undervalued during extraction and overvalued upon export, reducing taxable income. “The valuation of what exists in our natural resource sector is often underestimated. The manner in which companies operate in this sector tends to result in undervaluation when resources are discovered or extracted, and then overvaluation when they are priced and exported out of the continent,” Braganza noted, particularly highlighting issues in countries like Ghana and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

- Transfer Pricing: Related companies manipulate costs to minimize tax liabilities in high-tax jurisdictions. “Companies trade and transact with each other through something known as transfer pricing, where two companies that are part of a larger corporation trade amongst themselves and assign different costs based on the company’s jurisdiction,” he added.

Braganza further distinguished between IFFs caused by tax evasion and those by corruption or crime, noting, “Yes, there is a difference between the two.

The term ‘illicit’ is used because it incorporates deliberate immoral behaviour by individuals or businesses looking to bend the law to its breaking point.

Tax evasion, corruption, illegal proceeds, drug smuggling, arms smuggling, and human trafficking are all forms of illicit financial flows since they are illegal and violate the law.” He highlighted that while tax evasion exploits legal weaknesses, corruption and crime are outright illegal, both contributing to the drain of resources.

These outflows nearly match the combined inflows of official development assistance ($48 billion) and foreign direct investment ($54 billion), forcing governments to borrow to cover deficits, thus deepening the debt crisis.

Curbing IFFs could significantly fund development, potentially halving the $200 billion annual SDG financing gap (Africa Renewal). The 2015 High-Level Panel

Report on IFFs, led by Thabo Mbeki, recommends national and continental interventions, including greater transparency, beneficial ownership registers, and robust tax policies.

Despite some progress—African countries generated €1.7 billion in additional revenues by tackling tax evasion from 2009 through 2022 (AfDB Press Release)—the scale of IFFs remains a significant barrier to development.

Case Study: Ghana’s Extractive Sector

Ghana, rich in gold and other minerals, exemplifies the challenges of IFFs in the extractive sector. Braganza proposed five measures to enhance transparency and accountability:

- Domesticate the African Mining Vision: Align extractive sector management with continental development goals, adopted by all African Union member states.

- Enhance Parliamentary Oversight: Establish committees to monitor government and corporate activities, ensuring accountability.

- Public Beneficial Ownership Registers: Ensure transparency on company ownership to track revenue flows and tax contributions, crucial for transparency.

- Robust Tax Policies: Design fiscal regimes prioritizing national interests, including taxation, cost recovery, and minimization regimes favoring Ghana and its people.

- Understand Corporate Structures: Investigate subsidiaries in low-tax jurisdictions or under double-tax agreements to maximize revenue collection.

Ghana has made strides through the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, but implementation gaps persist. These measures, if effectively executed, could significantly reduce IFFs and boost domestic revenue.

The Role of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA)

The AfCFTA, operational since January 1, 2021, connects 1.3 billion people across 55 countries with a combined GDP of $3.4 trillion (World Bank AfCFTA). By April 30, 2025, 48 countries have ratified the agreement, aiming to boost intra-African trade, currently at 17% compared to 69% in the EU (LSE Africa).

Braganza sees the AfCFTA as a catalyst for development, fostering domestic resource mobilization and reducing external borrowing. However, teething problems, such as harmonizing e-commerce and investment policies, pose challenges.

If fully implemented, the AfCFTA could raise incomes by 9% by 2035 and lift 50 million people out of extreme poverty (World Bank Trade).

Even countries without particular products to export can benefit from the AfCFTA by participating in value chains, production, and manufacturing. Additionally, women stand to gain significantly from increased trade opportunities and economic empowerment within the free trade area.

Braganza stated, “Even if a country does not have particular products to export, it will still be involved in a chain of contributions—be it through production, manufacturing, or value addition. All countries will play a role within the framework of the trade area. Ultimately, service-related contributions will be equally significant to product-based benefits.”

Reforming the Global Financial Architecture

The global financial architecture is outdated, failing to address Africa’s multi-polar challenges.

Braganza called for a comprehensive debt reform package, including a platform for collective debt negotiations. The 4th Financing for Development Conference in Seville, Spain, scheduled for June 2025, is a pivotal opportunity to advocate for these changes (African Arguments).

Proposals include a UN framework convention on sovereign debt to shift power from institutions like the IMF to more inclusive bodies (New Debt Deal). South Africa’s 2025 G20 presidency could further these reforms, focusing on IMF governance and sustainable debt restructuring (SAIIA IMF and Sovereign Debt Reform).

Braganza emphasized the need for reform: “Reforming the architecture starts at the national level. We need a national agenda on what we want to transform and change. For example, debt negotiation is a negotiation between our government and lenders. Without a proper agenda regarding what we are borrowing for, how we manage it, and how we negotiate terms and conditions, we are likely to end up with unfavourable loan contracts.”

This domestic agenda extends to regional economic communities like the East African Community (EAC), Southern African Development Community (SADC), Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), and Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), striving for deeper political, economic, and social alignment.

Internal Debt and Domestic Borrowing

Braganza also addressed the issue of internal debt, noting that many African governments are increasingly borrowing domestically at higher costs than external loans, sometimes almost double.

This can crowd out private sector credit, hindering job creation and industrialization.

He suggested reducing commercial banks’ holdings of government securities to free up credit for businesses, stimulating economic growth.

He warned, “The domestic carrying capacity of private banks and commercial banks domestically to buy or hold government paper is very problematic because it crowds out the ability of private sector to access these financial resources and these credit lines in order to invest and build industry, build manufacturing and so on and so forth.”

This highlights the need to track domestic debt to ensure it acts as a stimulus for economic development rather than increasing vulnerability in domestic financial markets.

Borrowing Limits and Debt Sustainability

When asked about borrowing limits from institutions like the World Bank and IMF, Braganza explained that limits are specific to each country, often determined by their quota share or voting share within the IMF.

Domestic legislation typically governs borrowing limits through debt-to-GDP ratios, which vary from 35% to 70% for African countries, compared to advanced economies that may exceed 100% due to higher debt-carrying capacity.

However, he cautioned that these ratios can be bypassed, advocating for a debt-to-tax revenue ratio to ensure tax revenues are not overly diverted to debt servicing.

He stated, “There should be a specific amount of money that is allocated to just debt servicing as a proportion of the tax revenue. The reason for proposing this is to avoid governments from entering the trap of allocating significant amounts of their tax revenues to debt servicing, as we are currently seeing across the continent, because that means then they are diverting tax revenues away from development and public services in order to service debt; thereby undermining development and achieving Agenda 2063.”

Looking Ahead: Pathways to Sustainable Development

Africa’s sustainable development hinges on addressing its debt crisis, curbing IFFs, and leveraging the AfCFTA. Braganza’s vision requires coordinated action at national, regional, and global levels. Civil society, media, and policymakers must advocate for transparency, robust policies, and fair financial systems.

The 2025 Year of Reparations, declared by the African Union, and the Pope’s Jubilee Year for debt forgiveness underscore the urgency of these reforms.

By mobilizing domestic resources, reforming global finance, and harnessing regional integration, Africa can achieve Agenda 2063 and the SDGs, fostering a prosperous future for its people.

Braganza concluded, “Thinking through how we are going to deal with these challenges and how we catalyze opportunities presented to us through Agenda 2063 is extremely important if we expect to get any meaningful negotiated outcome from the 4th Financing for Development conference taking place in Spain later this year.”